We moved this past December, and part of getting settled into our new home these past few months has been setting up some new flower beds. Of course, I dug up many of my iris bulbs and planted them in their new home. These bulbs are descendants of ones that grew at my Nashville home going back 16 years now. Despite the terrible timing of being dug up in late December, they are doing well, though I still have my doubts about them blooming next spring. They may skip a year like they did when they made the move with me from Nashville.

We have tried to start small this first year with garden plans and just created our front flower beds around the porch and started a small shade garden that will be expanded over time. But I also wanted to do a small cutting garden this year, so I planted a very small patch of zinnia seeds in early June and they have taken off beautifully. After seeing their success on a small scale, my husband is making plans to tiller up half the yard next year to create a hummingbird/butterfly sanctuary. We are getting quite ambitious around here.

The butterflies have loved the zinnias and every time I have looked out at them this week, there are multiple butterflies happily hovering over the blooms, going from flower to flower. I took some pictures of them, and I was struck by how just a couple of months ago, the small patch of land was just a plain stretch of grass, but an afternoon of digging and $5 worth of seeds had turned it into a small butterfly haven.

This got me philosophical and I started to look up poetry about butterfly gardens- there’s a lot out there. While our metamorphizing winged friends are obliviously flying from flower to flower, we humans have endowed them with lots of symbolism and spiritual meanings. Poets have been inspired by them as long as poetry has been created.

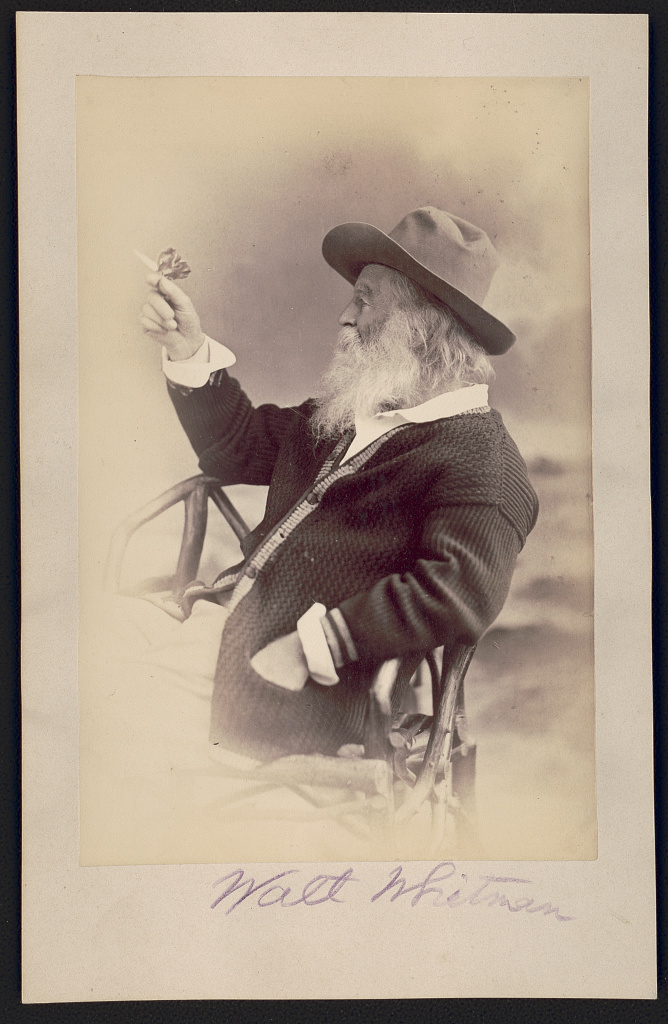

This internet road led to Walt Whitman’s poetry and the story about his most famous photograph.

In 1877, Whitman was photographed holding a butterfly aloft. People close to him recalled it being his favorite picture of himself. Whitman told his biographer, Horace Traubel, “Yes, that was an actual moth. The picture is substantially literal; we were good friends. I had quite the in and out of taming, or fraternizing with some of the insects.” He also told historian William Roscoe Thayer, “I’ve always had the knack of attracting birds and butterflies and other wild critters.”

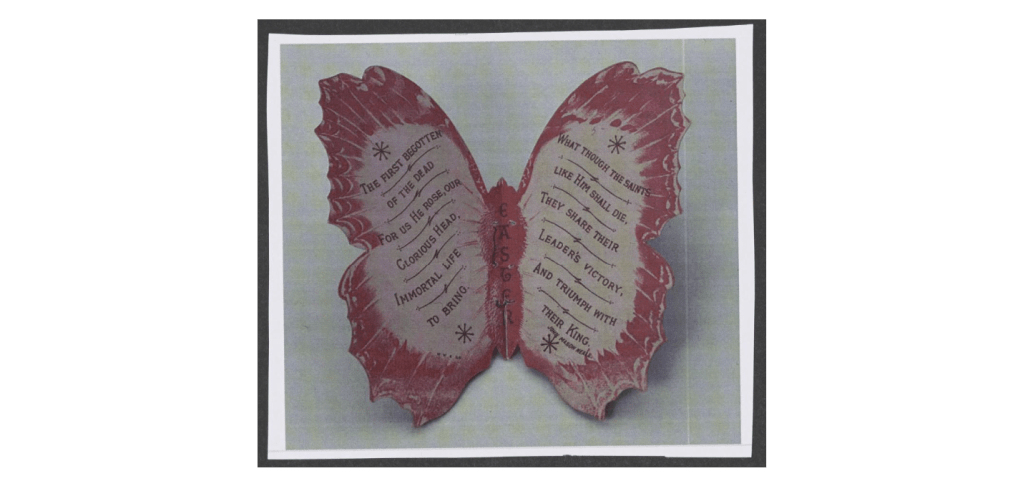

The catch with this picture? The butterfly was fake. It was a cut out of a butterfly from an easter card that he tied to his finger. Move over Instagram models. Walt Whitman was carefully cultivating his image with trickery long before you.

A butterfly on the hand was a recurring motif in his later editions of Leaves of Grass and it appears he meant to use this photo as cover art for his book. It’s unclear if he was trying to really pass himself off as one with nature at all times or if he was joking with the people he told the butterfly was real.

His cardboard butterfly has its own interesting story. The cardboard prop was tucked into one of his notebooks that was donated to the library of congress in 1918. Following the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1942, the Library of Congress shipped many of its most valuable holdings to various locations for safe keeping and Walt Whitman’s notebooks were sent to Ohio. After the war, the crate with his notebooks was sent back to Washington, but when it was opened, it was discovered that several notebooks were missing, including the one with the cardboard butterfly.

Fast forward to 1995. A New York lawyer walked into Sotheby’s with four notebooks for an appraisal. He was settling his father’s estate and said that the books had been a gift to his father over 30 years ago. The cardboard butterfly in one of the notebooks helped Sotheby’s to identify the notebooks as part of the missing collection from the Library of Congress and the lawyer returned them to the Library of Congress when he learned their history.

It’s rather amusing if Walt Whitman was indeed trying to pass his butterfly off as real because the journey that little piece of cardboard went through ensured that it was well documented for all the world to see for the artifice that it was. When the missing notebooks were returned to the Library of Congress, the FBI who had been called in to help recover the missing notebooks, photographed all the contents and escorted the notebooks back to Washington where the Library of Congress recorded all the contents digitally. This was part of the library’s new initiative at the time to make their collections available to the public on the internet. And that is now where everyone can see the butterfly.

With Walt Whitman being such an important figure in American literature history, scholars have poured through all of his work, journals, and everything acquaintances wrote about him to gain a better understanding of the man. But so much of his life and motivations remain a mystery. One thing that is clear is that he was someone who had a sense of marketing himself, and he went as far as to anonymously publish reviews of his own work as part of his self-promotion.

Sometimes I worry about raising a child in this social media era of deceptive marketing and content creators who prey on people’s insecurities by presenting unrealistic pictures of perfect lives or fake scenarios. But then Walt Whitman reminds me this is nothing new under the sun. People have presented curated images of themselves to others since the dawn of time. The internet just gave everyone a new medium to practice this.

As for Walt Whitman, I don’t blame him for wanting to add to his art by portraying himself, the poet, in a certain light. His writing held an optimism to it, even when he explored bleaker themes such as death and war. Amongst the notebooks that were returned to the Library of Congress, there were some journal entries from Whitman’s time as a Civil War nurse and notes from his visits with soldiers in a Washington hospital.

“bed 15–wants an orange. . .bed 59 wants some liquorice. . .27 wants some figs and a book.”

He witnessed great sorrow, suffered losses, and lived through a time when the democracy that he so believed in and championed in his writing was being direly tested. In the end, the image he wanted to project of himself as he promoted his work was of a poet who was one with nature. He chose to bring the focus on beauty and simplicity.

So why are we so intrigued by butterflies? What is it about them that has made us create so many ideas of symbolism around them? Almost every culture has depictions of butterflies as representative of the soul and symbols of deeper meanings such as love, freedom, and transformation. Many believe that they come to us as spirits of those who have passed on or as messages from the universe.

Caterpillars aren’t the only animals that undergo such a dramatic metamorphosis, but butterflies are probably the animal many of us see most often in our day to day that was previously an entirely different creature. And they can fly in the end. It’s not hard to see why they have been bestowed with great symbolism. Or why poets like Walt Whitman have been inspired by them as long as humans have scribbled verse.

So thank you, August garden, for bringing more butterflies my way this year and leading me down this little research path contemplating beauty, transformation, and all the little complex ways we humans interact with and present ourselves to the world.

Leave a comment